This is Poland

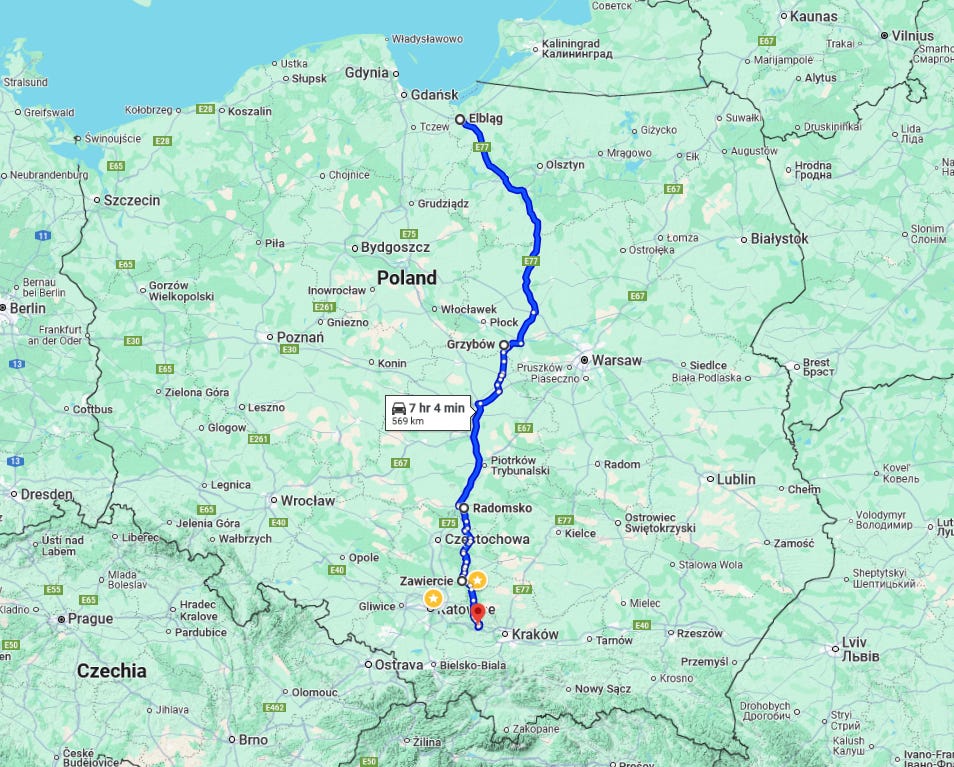

600 km in the search of Elbing Gate, the mythical Kujawiak and the soul of the country

I live 20 minutes from Kraków, the world-class tourist hub. Despite the stunning beauty that surrounds us, I have never seen a foreigner in my village. Ever!

In this story, travel with me to five other places that rarely see strangers.

Last week, we decided our living room needs a door to separate it from the kitchen. A wooden, semi-transparent, sliding door. Not an easy thing to find second-hand. But I found it—online. In Elbląg, someone was refurbishing a house and giving away a wooden sliding door. Exactly what I wanted.

But Elbląg is 600 km away. Way too far for a casual drive. Unless… your friends are gathering nearby for a music meeting.

In fact, they are. Exactly on my route. Coincidence?

I resolved to go.

With the route in place, I decided to make the most of it.

To dismount the door, I’d need an angle grinder, a circular saw, and a cordless screwdriver. I didn’t have any of these—but I trusted OLX, Poland’s second-hand classifieds market. Believe me, searching for classifieds along the route works.

Let the journey begin.

Zawiercie

My first stop is the inconspicuous town of Zawiercie. I park near a communist-era block of flats, ring the doorbell, and ride the elevator to the fifth floor to meet Kamil. After a handshake, he explains he has just finished renovating the apartment.

“I won’t use the tools anymore—let’s find someone who will,” he says with a smile, handing me a brand-new angle grinder for 150 PLN, a quarter of its original price.

I take some time to explore the town. Zawiercie is an emblematic small industrial town, a silent witness to history. It flourished a hundred years ago during the industrial boom. A massive glassworks was built here, and the town thrived thanks to an influx of migrant workers.

After WWII, the communist regime installed by Soviet Russia prioritized industry and courted workers with privileges, hoping to secure their political support. They miscalculated badly: Polish workers—stubborn, skeptical of any authority—became the backbone of resistance movements that eventually helped topple the regime in 1989.

Sadly, towns like Zawiercie paid the highest price. In the era of economic transformation, they were neglected by Warsaw-based governments obsessed with macroeconomic indicators. After two decades of unemployment and poverty, these towns of hard-working people are slowly becoming prosperous again.

All of this can still be seen in Zawiercie, if you know how to look.

The former seat of Huta Zawiercie (the glassworks) looms over the pond. The “socrealism” architecture of the 1960s often tried to evoke medieval castles—but the result is more cheap than noble, more grotesque than grand.

Not far from there, a stand-up comedy poster clashes with a solemn historical mural. In 2016, the old glassworks factory declared bankruptcy and stopped paying its workers. In a desperate move, the factory began offering glass products instead of wages. Widespread suspicions of nepotism, mismanagement, and corruption sparked mass protests among the workers. They achieved nothing. Only bitterness remained—bitterness and the feeling of being forgotten by the government once again.

The nearby pond holds industrial water, unsuitable for bathing. Where an Englishman might put up a sign saying simply “No entry,” a Polish official feels compelled to write a full essay. We even have a tongue-in-cheek term for it: regulaminoza—an imaginary mental disorder that afflicts certain public administrators. They believe every pond, every square, and every playground must have a detailed set of rules (regulamin). Regulaminoza is as contagious as COVID-19. Learn the word, and your Polish friends will pat you on the back. You’ll be seen as one of us.

I drive slow, stopping often, talking to people and taking pictures. I feel that in Zawiercie, every corner asks for a photograph. History is everywhere. There are no tourists. Tourists avoid places where there are no other tourists.

Radomsko

The visit to Zawiercie pushes my navigation onto a country road. I’m glad—because nothing ever happens on a highway. I continue toward Radomsko, another small town.

In the central square of Radomsko, I enter a second-hand shop that had listed a circular saw. It costs only 100 PLN. I linger at the square and chat with the locals, mostly pensioners. I can tell the air here is different. Life feels good.

Radomsko was one of the winners of the economic transformation. Conveniently located near several major highway junctions, the town has become a logistics hub for many businesses—including Jysk, the Danish furniture company, which built an enormous storage facility serving all of Central Europe.

But where the new settles in, the old often refuses to disappear. In the nearby village of Święta Anna (Saint Anna), I spot a dinosaur: an old-style gas station, a relic from the times when gas stations were still family businesses.

There aren’t many of those left. Most perished in the uneven fight against corporate giants like Orlen, Shell, and BP. They also earned a shady reputation—allegedly, some private owners were tempted to mix water with gasoline to boost their margins. Or so the urban legend goes.

Łódź

Radomsko is only an hour from Łódź, my next stop. I drive slowly through the outskirts of this major city, historically tied to the textile industry—with all its booms and busts—much like Manchester or Roubaix in France (see my earlier story on Roubaix!). Unlike Roubaix, though, Łódź leaves a positive impression.

In a suburb, I pick up my final deal of the day: an electric screwdriver from Katarzyna. She comes down from her home and meets me in the garage, which also doubles as her storage space. We end up having a long chat, and she tells me about her life. She’s a small business owner—energetic, talkative, and full of optimism. I ask her about a saying I heard two decades ago from a rather depressed Łódź resident:

"Kto mieszka w Łodzi, sam sobie szkodzi"

(He who lives in Łódź, is bound to lose.)

Katarzyna laughs. “With that kind of attitude,” she says, “you’re bound to lose no matter where you live.”

In the late 19th century, when Poland was under Russian occupation, Łódź was the most industrialized city in the entire Russian Empire. Fortunes were made here, fast. Today, not much remains of that former glory. On my way out, I pass the tiny “Textile Center”—a modest echo of what once was.

My next stop is a village near Łowicz, where I’ll stay the night. But I’ll return to that later—since it’s the most important part of the story.

Elbląg

The next day, I drove four more hours and reached Elbląg, where—together with the owners—we dismounted the door and figured out how to fit it inside my van. It wasn’t easy. The operation took several hours. (See the image below, and you’ll understand why.)

At the end, tired as dogs, we sat down to drink some water.

“I think I’ll hang a big label in my living room,” I said. “The Door From Elbląg.”

“No… The Gate of Elbing!” the landlady corrected me with a playful wink, alluding to a certain famous story known by the locals.

The Story of the Gate of Elbing

Most aficionados of medieval European crusades have never heard of the one crusade that was, sadly, successful. In 1226, with papal blessing, the Christian knights of the Teutonic Order arrived in what is now northern Poland, tasked with converting the last pagan corner of Europe: the wild tribe of the Old Prussians.

The mission was “successful.” Within two generations, an entire nation had been not converted, but annihilated by the Christian knights in a campaign of terror and savagery. The genocide of the Prussian people was complete in less than fifty years.

After wiping out the Prussians, the Teutonic Knights established their own state—something akin to the Crusader states in Palestine—and became a belligerent neighbor to the Kingdom of Poland. In the name of Christ, they launched raids that devastated borderlands. One town that often suffered was Elbląg, also known by its German name Elbing. Both names were used interchangeably. Like most Polish cities in the Middle Ages, Elbląg was multiethnic—German, Latin, Yiddish, and Armenian were widely spoken.

On an early morning in 1521, two thousand Teutonic Knights approached the town of Elbing under cover of fog and stormed through its open gates. A 15-year-old baker’s apprentice (piekarczyk), on his way to the morning shift, was the first to notice. With no one else around to help, he ran to the Gate of Elbing and cut the ropes holding up the portcullis—the heavy iron gate that moves vertically. The gate crashed down, slamming shut just in time to block the attackers. His quick thinking saved the town.

Piekarczyk became a folk hero. Whether the legend is true or not is debated—but many other defenders from the war of 1521 are known by name. The defense of the entire district (Warmia) was led by none other than Nicolaus Copernicus, the famed astronomer who first proposed the heliocentric model of the solar system. He was also a skilled administrator and loyal subject of the Polish king.

So that’s the reference to The Gate of Elbing.

But to me, my wooden door from Elbląg has another meaning: that’s why I came.

The Elbing Gate is my reason—or my excuse—for the journey.

In the end, the Door from Elbąg finds its place in my campervan, leaving even some space for me to sleep next to it. I drive back to Łowicz where I will spend my second night.

Łowicz

Northern Poland is all forest, meadows, and nature. Open spaces. Tiny, forgotten villages. Again, I avoid the highway. The country road is pleasant, and leaves space for an adventure, which highway does not.

I finally reach my destinaton: Grzybów, a tiny place near the town of Łowicz.

That’s where a group of young people, fascinated by the archaic music tradition of the region, gathers each year to learn, play, dance and experience (this website lists similar events).

You can’t understand a country through words alone. But you can experience it. To experience Poland… learn to dance kujawiak. Many of us, dancers, would agree: there is something magical about it. Certainly worth traveling 600 kilometers for.

The kujawiak is not just a dance—

it is a whisper of wheat fields swaying under the golden dusk,

It is the lull of grandmother’s lullaby,

It is Poland dreaming in 3/4 time— melancholy, graceful, proud.

And when it is danced well, the floor becomes a field, and the dancers become the wind.

Buckle up—eight minutes of slow, steady beauty, played by Mateusz, Agnieszka and Kuba (my own recording).

Post Scriptum

Next time you visit Poland, promise me one thing: skip pierogi on Kraków’s main square. Better yet, skip any town featured in tourist guides. Instead, find your Elbing Gate: your reason to travel.

Go to Zawiercie, Radomsko, and Łódź. Go to Elbląg and Łowicz.

Pay special attention to post-industrial towns: that’s where the heart of the country beats.

Then, go to traditional music gathering in a tiny village, and learn to dance kujawiak.

Breath in forests.

Swim in lakes.

Fish in rivers.

This is Poland.

Dang, some of these pictures look like sets from the later Universal Soldier movies. 😉 Thanks for taking us around. 🙏

very nice read and a road trip worth discovering! funnily enough this is the type of trips we make every august in poland and just now we arrived in Elblag! excited to looks around in the next few days!