I am in Ukraine. Three images, all from the same day.

Cemetery. Perhaps two hundred fresh graves, each marked with a Ukrainian flag. Four more are being dug as I watch. This isn’t a major town - just a quiet village an hour from Poland, far from the front.

***

In Velyki Mosty, a small town, an old man in uniform approaches with a smile: “I will tell you about Bandera. Do you know of him?”

I do. But do we share the same story? A shiver runs down my spine.

***

In Lviv, a city with a tangled Polish-Ukrainian past, a young soldier named Mykola stands behind a street stall. On display: munitions, broken drones, and spent shells. He’s raising money for his brigade.

We talk because we’re here for the same cause. We’re delivering another firefighting truck, part of a grassroots network of thousands of ordinary, unnamed people. Each connection strengthens the web. The next truck will go to Mykola’s brigade.

The Love - Hate Brothers

Poland and Ukraine share a thousand years of history - raids from all sides, shifting borders, and grudges carried across centuries.

Poland eventually stabilized, thanks partly to the stubborn Prince Łokietek, twice ousted from Kraków, forced to live in a cave, yet returning each time until he outlived all his oponents and became king at 60 (in 1320). Ukraine, meanwhile, endured Tatar raids, then centuries under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where nobles amassed vast wealth while peasants lived in near-slavery. Many Polish serfs fled east to become free Cossacks in the borderlands.

Ukraine literally means “borderland.”

The memories remain - romanticized and bitter. Poles see Cossacks as free riders of the steppe; Ukrainians see Poles as organized and advanced - but also as centuries-long oppressors. And Poles remember the cruelty of Ukrainian militias.

Once, trekking in Ukraine’s mountains, I met shepherds living as they had for centuries - an open fire in the middle of the hut, smoke venting through the roof. They offered fresh sheep cheese, songs, and a bed for the night. The hut was too tiny so we instead pitched our tent outside, to which one shepherd joked: “polskye pany” - Polish nobility.

These 16th-century grudges have little to do with today. Most Polish nobles weren’t even ethnically Polish, and the nobility itself was wiped out in wars or driven into exile. Around 90% of today’s Poles descend from serfs - many of whose kin escaped to Ukraine. The two nations have much more in common than some want to believe. Yet nationalist narratives on both sides still frame it otherwise.

***

Towards 18th century, Moscow stepped in and Poland was no more. Ukrainian free cossacks were forcibly conscripted to tsarist army with 25-year service - in practice, life sentence. Together with thousands of Polish prisoners, those men formed the backbone of the Russian forces that subjugated vast areas of Asia, for the glory of the tsar.

Crowdfunding Reality

Fast forward to 2025. Each week, old but sturdy Polish fire trucks cross into Ukraine. They have no electronics, can be fixed in the field. They save lives on frontline. This is not a government initiative. The trucks are decommissioned from fire stations, bought by crowdfunding, repaired and delivered by volunteers. It’s a vast, decentralized network - people with day jobs who spend evenings helping.

But trucks are only part of it.

Anti-drone nets are now the main focus. They save more lives per dollar spent. In 2022, when Russian army started hitting Ukraine with drones the Polish fishermen were first to react - and donated tons of old fishing nets, perfect for stopping drones. When supplies ran out, nets arrived from Dutch and Danish fishermen - and later from French vineyards.

While the network is international, most of my Western friends are unaware of this and usually don’t grasp the scale of this work - or how normal it is here for soldiers in Ukraine to fundraise on the street. Imagine a U.S. Marine on leave, asking passersby in Central Park for money to buy munitions… unthinkable. In Lviv, it’s everyday reality.

Crowdfunding is an essential part of Ukraine’s war effort. Every net, every truck, every bandage counts.

Crowdfunded victory: 1920

A skeptical reader on my previous story commented: “Crowdfunding to stop an army? Be serious.” Yet it happened already. History offers a striking parallel.

In 1918, Poland regained independence after 123 years of partitions. It was short-lived. Only two months later, the Soviet Red Army invaded again. For Poland, this was the eighth full-scale Russian invasion (after 1654, 1717, 1733, 1792, 1794, 1831, 1863, 1914). Poland was doomed to fail, with newborn army of 30,000 men against 700,000 Soviet troops.

There was no national currency, no gold reserves, and no foreign ally ready to commit funds.

The government set up the Military Purchasing and Transport Mission (Polska Wojskowa Misja Zakupów, PWMZ) in Paris, to buy weapons from the West. France offered a credit of 425 million francs and the offered U.S. $50 million - but not in cash. Both loans were to be spent only on goods supplied by the lender. The French offer turned cynical: overpriced, often broken, and obsolete surplus from World War I. The first 185 million francs’ worth of equipment was billed at 330 million.

While the situation of the Polish army, outnumbered 1:20, became desperate - in Paris, weeks of negotiation failed. In the end, the Mission turned down the French offer and turned to other countries: Italy, the UK, Greece. But time was running fast.

The U.S. credit terms were fairer but required gold backing, which Poland didn’t have. The solution came from its citizens. In January 1919, the National Treasury (Skarb Narodowy) began collecting gold, silver, jewelry, and cash. From peasants to industrialists, people donated wedding rings, family heirlooms - anything of value. In less than a year, $45.8 million was raised. The diaspora joined in, raising $19 millions more.

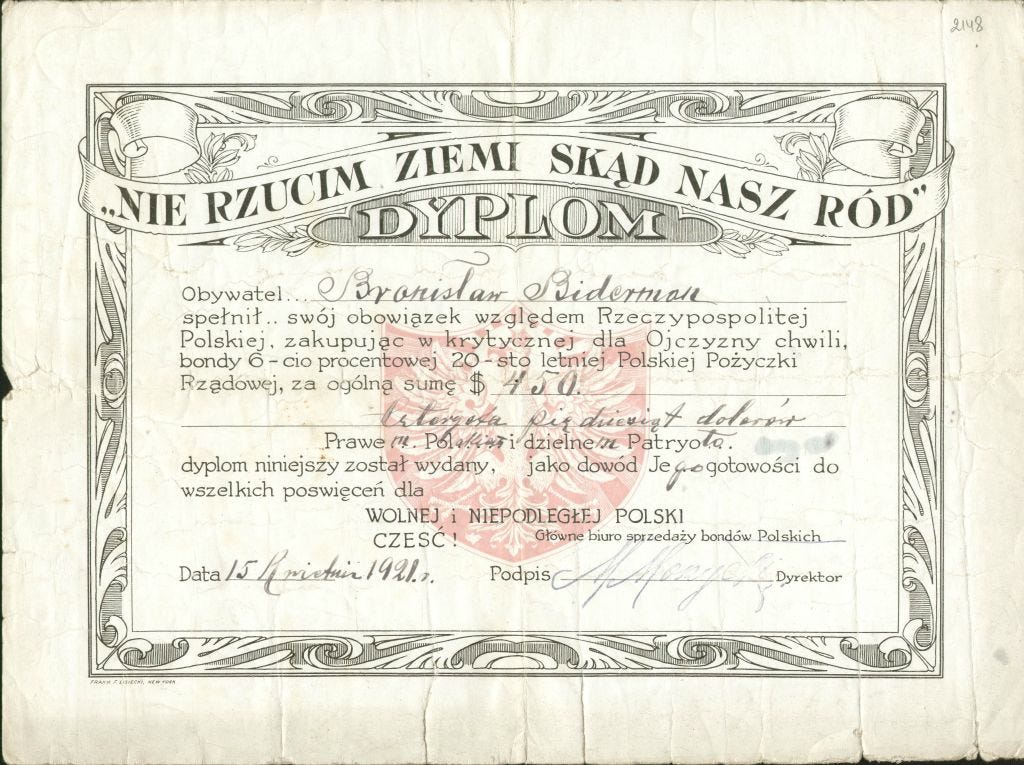

Officially, the loan was to be returned after 20 years. But no one had illusion: chances for survival of the Polish state were slim. The language of certificates issued to donors made this clear. One read:

"WE SHALL NOT ABANDON THE LAND OF OUR ANCESTORS"

Citizen S. Bronisław Biderman has fulfilled his duty to the Republic of Poland

by purchasing, in a critical moment for the Homeland, 6% twenty-year Government Bonds

of the Polish Loan for the total amount of $50.00 (fifty dollars),

thus showing himself to be a true and brave Patriot.

This diploma has been issued as proof of his readiness for any sacrifice for

A FREE AND INDEPENDENT POLAND

In less than a year, Poland had amassed 4.5 tons of gold. The Paris mission used it to back loans and purchased massive quantities of arms: nearly 775,000 rifles, 1400 artillery pieces, 100 million munitions, 316 aircrafts, 2349 vehicles, 18 armored vehicles, and over 1.7 million pairs of boots and military uniforms, and large quantity of medical supplies.

By September 1920, the Polish army had grown to nearly 950,000 troops, halting the Soviet advance. A nation’s determination to crowdfund its own survival had stopped an empire.

Western Aid and Chaotic Networks

It’s tempting to frame these past events contrasting brave Poles to cynical West.

Not so simple.

One man remembered in Poland is Herbert Hoover, an Iowa-born Quaker, engineer, humanitarian, and future U.S. president. In 1919, he visited Warsaw and was greeted by 25,000 barefoot children thanking him for American Relief Administration aid. They waved their tin cups and American flags. A witness of the event reports that these children knew Hoover’s name. He had become a hero to them. Hoover saw their poverty and ordered 700,000 pairs of shoes and coats before winter. By 1922, his operations had also delivered half a billion meals and $250 million in aid, saving millions from starvation.

Today’s volunteer networks in Ukraine mirror that mix of chaos and urgency. There is no central command, only countless small groups and personal contacts scattered across Ukraine, Poland, Europe and beyond. This is deliberate: direct channels are trusted, while larger organizations risk delay, infiltration, or corruption.

Even respected institutions can fail. One of bigger scandals came from Red Cross. Early in the 2022 war, we urged friends abroad to donate to the International Red Cross, to help Ukraine. We later removed their link, after widely reported allegations of their cooperation with Russian forces and support for organizations deporting Ukrainian children.

Low-key communication isn’t foolproof either. A few months ago, an old acquaintance, Tatyana, contacted us for medical aid funds. When we asked which brigade the supplies were for, she became evasive and stopped replying. Most likely, the account had been hacked - or someone was simply fishing for cash.

The 1920 Alliance and Its Collapse

Poland-Ukraine alliance is not a new idea. In 1920, Poland's marshal Piłsudski and Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura forged an anti-Soviet pact, aiming to free both nations. In the presence of Ukrainians, Poles and Jews, Piłsudski said: ‘Hear my call on behalf of Poland: Long live free Ukraine!’ Joint forces took Kyiv in May, but support of the local population was weak: war fatigue prevailed.

But the real blow came from the West.

Soviet intelligence worked relentlessly to sabotage Poland’s supply lines, spreading propaganda in Western Europe that painted Soviet Russia as the workers’ state and Poland as an oppressor. This message resonated with dockers, railwaymen, and laborers in France, Britain, Austria, Greece, and Germany, sparking strikes, protests, and sabotage. And it worked. France froze Polish arms in its ports; Czechoslovakia blocked rail transport. Austria and Germany joined in, with strikes and exorbitant transit fees. Only a narrow rail link through Hungary kept the faction of supplies moving.

Starved of resources, Poland retreated, and most of Ukraine was lost to the Soviets. The 1921 Treaty of Riga ended Polish support for Petliura. Visiting imprisoned Ukrainian officers later, Piłsudski said: “I am so sorry, gentlemen. It was not meant to be.”

***

Piłsudski returned to power in a 1926 coup. Mysteriously, only a few days later, Petliura was assassinated in Paris. Someone clearly intent on preventing any revival of the Poland-Ukraine alliance.

The crowdfunding that saved Poland could not save both nations. Millions of Ukrainians would later perish in the Holodomor.

***

A month ago in Lille, I spoke with French friends - mostly on the far left. Over beers, they insisted Russia was an honest country besieged by NATO. I asked if they, as French socialists, accepted responsibility for the millions who died in the Holodomor, after the Soviets retook Ukraine - enabled partly because French dockers blocked arms shipments to Poland in 1920. They were stunned; they had never heard the story. Silence, then disbelief. The next day, between smoking cigarettes and singing revolutionary songs, they repeated their support for Russia.

Do you want to hear of Bandera?

In our journey, we stop on a provincial town square. An old man in uniform approached me during a military fundraiser. “I will tell you about Bandera. Do you know of him?” he asked warmly.

A shiver comes down the spine.

For a Pole, it is the most dreadful question. Stepan Bandera, Ukrainian leader of the radical OUN-B faction in the 1930s–40s, is tied to the Volhynia Massacre—mass ethnic cleansing that killed an estimated 50,000 Polish civilians in 1943–44, often with unimaginable cruelty.

Only two weeks earlier I was waiting to a doctor in Poland. In the line, a quarrel exploded between a Polish middle-aged gentleman and an immigrant Ukrainian lady. The man, all agitated turned to me exclaiming: "we will never get along with them. My grandmother told me". Everyone in Poland knows what this ominous phrase means: in many Volynha villages raided by Ukrainian militia in 1940’s, only a few children survived. Many years later, as old people, they spoke to their grandchildren of the cruelty witnessed. For Poles, Bandera is not a freedom fighter who someone who inspired massacres.

In western Ukraine, however, Bandera is often seen as a symbol of defiance against centuries of occupation—many unaware of the massacres. Ukrainians also point that Bandera himself was in German custody for much of 1941–1944, and the massacres were led mainly by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), not directly by him. Two incompatible truths coexist: one man’s patriot is another’s war criminal.

I look at the veteran. He appears honest, inviting and clearly meant no harm. He is thankful to Polish support, and shares Ukrainian and European flags…

What to do?

We stop to chat and share some kind words.

***

A week after our meeting with the veteran, on the exact day of Volhynia massacre anniversary, Russian missiles struck the Volhynia region. Officially a coincidence.

But it is no coincidence. Today’s Polish–Ukrainian brotherhood is especially bitter for Russia. All means are used to divide and shift the narrative on what divides the two nations.

After Maidan: A Brotherhood Moscow Cannot Bear

In recent decades, something remarkable happened between Poles and Ukrainians. After generations of silence, mistrust, and unspoken trauma, the relationship turned — not with official treaties or speeches, but through ordinary people.

When Ukraine rose during the Orange Revolution in 2004, thousands of Polish volunteers crossed the border — students, journalists, lawyers, and priests. They brought tents, food, legal aid, and cameras. They stood beside Ukrainians on the frozen streets of Kyiv, lit candles in solidarity, and gave them the only thing that truly mattered at the time: the feeling they were not alone.

Ten years later, as Russia annexed Crimea, invaded the Donbas, and then launched a full-scale war, Poland quietly became home to an estimated three million Ukrainian refugees. They worked in our factories, cared for our elderly, studied in our universities. Many Poles came to know their Ukrainian neighbors not as ghosts of the past, but as baristas, builders, nurses, mothers. Poland's economy benefitted enormously.

Yet this unprecedented closeness has again become a prime target for Russian disinformation. In Polish social media, familiar whispers have returned, often initiated from anonymous accounts: They’re taking your jobs. Ukrainian women are taking your husbands. And they never apologised for the Volhynia massacre. These words are calculated to sting, divide, and reopen old scars.

Now politics joins the game. Newly elected Poland’s president Karol Nawrocki declared he would block Ukraine’s NATO bid. One of my Substack commentators, clearly unaware of the context, wrote: “Poland should know better.”

Yes, Poland knows better. Time and time again, the blows come from the West. Nawrocki, trailing in the first round of presidential election, won by just 1% after an unexpected endorsement from the President of the United States. Then, his anti-Ukraine declaration, against all logic, shocked nearly everyone. Why did he say it?

Was it… a contracted thank-you to Trump?

The Small Men

And so we come to the third picture. Mykola, crowdfunding for his brigade on the streets of Lviv.

How important is crowdfunding for the Ukrainian army?

United24, the Ukrainian government’s crowdfunding platform, reached USD 1 billion in 2025. Major Polish NGOs (Caritas, Siepomaga, PAH, Solidarni, ODF, PAFF) reported PLN 283 million raised. These funds make up around 4% of official international government-level military aid, estimated at USD 30 billion in 2022.

But these numbers are dwarfed by private initiatives run through informal networks of friends. People like Mykola in Ukraine, Ola in Poland, or Gosia from the Polish diaspora in the UK are never counted in official statistics.

And yet on top, there are official aid initiatives intentionally kept low-key. In early 2025, during a distasteful Twitter exchange, Elon Musk claimed he could cut off Starlink connectivity to the Ukrainian army. Polish foreign minister Radosław Sikorski reminded him that he could not, because the service had been purchased commercially and paid for by the Polish government. Enraged, Musk — by then a prominent DOGE figure — replied: “be quiet, small man. You pay a fraction of the real cost”. U.S. senator Marco Rubio soon followed, telling Sikorski to “say thank you”. Later, Zelensky himself was humiliated in a widely reported meeting with Rubio and Trump.

Rubio may have personal animosity toward Sikorski, married to Anne Applebaum, a journalist who exposed Trump-Russia links. But the USD 50 million in question isn’t Sikorski’s personal money. It represents what we stand for: overcoming centuries of hostility, trauma and distrust. Choosing what unites us, rather than what divides us.

Poland’s support to Ukraine represents collective effort of millions of “small men” — just as in 1920, when Poles donated wedding rings and heirlooms so rifles could be bought.

Be quiet, small man. Say thank you.

If that effort is small, then how small are the people from Opole, Poland who over years of unrelenting work have sent thousands of tons of anti-drone nets to Ukraine, saving countless soldiers they will never meet?

And how small are Valenti, Ola, Viera, Leonid? Or those boys, who will never speak again?

***

Big men, instead, operate on another level. In a shocking revelation by Reuters, already in 2022, Musk shut off access to Starlink for the Ukrainian army, causing operational and tactical damage - citing fears of a Russian nuclear response. How, when and why did Big Tech come to see itself as the arbiter of nuclear stability - is baffling.

What happens next?

It’s tempting to dismiss all Americans as arrogant and malevolent. But no. Idiots exist everywhere - just like heroes.

America is not only Rubio and Musk. America is also Herbert Hoover.

Poland is not only the heroic volunteers workers. Nationalism, fuelled by Russia’s propaganda, is undeniably on the rise.

And Ukraine?

Can I imagine Ukraine soon joining the EU and becoming a prosperous, democratic nation, committed to human rights, transparent business, and Western values?

Absolutely.

Can I imagine the opposite — Ukraine subjugated by Russia, its nationalism redirected against the West, its battle-hardened army soon marching alongside Russia in a “civilizational” full-scale war against Europe?

Sadly, yes. Easily.

What happens next?

Beautiful piece! Polish-Ukrainian relations are infamously complicated, but I love how basic truths and humaneness prevail in your writing. Thank you for that and for helping Ukraine!