Hunger in the Time of John

In 1947, amid devastating famine, an unexpected shipwreck brought life and death

In the Time of John (Tempo de John), the drought and hunger on the island was so severe that people ate their clothes and even the earth. Those who were still alive prayed. And a miracle came. A ship carrying enormous quantities of corn run aground near the island. Ship’s name was John.

The story is true. But let’s start from the beginning.

We are on Maio, a small island of Cape Verde, a tiny archipelago nation west of Africa. We are staying in Calheta, a small fishing village (more: Where Fishermen Use Wind or other Cape Verde stories).

One afternoon, we saw a tent nearby, so we went over to say hello. The five young travellers came from Praia, which is the capital town on the neighboring island. Piglets, belonging to our landlord Djoka, keep them company. We quickly made friends.

In Cape Verde you don’t need much time or effort to befriend people. Things happen naturally. Towards the evening, there came time for food, music and time together by the fire. I asked my new friends to share stories from long ago. Stories that were important.

Djony’s story

I never knew my paternal grandfather, because my father did not maintain relation with his dad. They were in long conflict. My grandpa lived in the same town as I did, Praia. However, he was in a distant suburb, and so I had never met him. But one Sunday, as teenager, I took a stroll with my dad, and we stumbled at my grandpa by pure accident. So my dad presented us.

My grandfather was radiant with happiness, unable to contain his delight. He hugged me many times. He then walked me around his district. We spent all day together, during which time he showed me much affection. He would also proudly present me to all his neighbors and family.

This was a heartwarming and very emotional day, which I will remember forever.

And this was also the last time I saw him.

A few days later, I learned that my grandfather died.

*** *** ***

Lina’s story

My grandmother lived on the island of Santo Antão. In 1947 grand famine came. People were dying. One day, an Italian ship was caught in a storm and crashed on rocks near Santo Antão. The ship carried a large stock of corn, for Italy. The ship was not intended to stop in Cape Verde, it just incidentally shipwrecked. The captain, drawn by compassion, allowed the starving people to recover the corn. People from Santo Antão took to boats and, notwithstanding the storm, for many days recovered all the cargo from the sinking ship (you must know that the sea near Santo Antao is extremely rough and violent).

That year, that ship catastrophe saved the island population. Otherwise, without that corn, we would have all perished.

*** *** ***

Dex’s story

Indeed, the tragic year of 1947 remains in memory of everyone. In the same year 1947, my grandmother, who lived in Praia, island of Santiago, lost a child - my uncle, who was then a small boy. The famine was enormous on all islands, including the island of Santiago. But the child died not because of famine. One day, international aid arrived to Praia. Everybody, even from distant villages, walked to Praia to benefit from the food distribution. Also my grandmother with her child walked.

Food was unloaded from the ship, and stocked in a large municipal storage building. The authorities planned to distribute it to the needy. But there were too many people. The starving pilgrims stormed the building, and too many people entered at once. The building was not designed to handle such a crowd, and it collapsed. My grandma survived, but her small boy did not. He was burried under the collapsed building and died.

*** *** ***

Touched by the stories, I later did some research. And I learned more about happened in 1947 - but the truth exceeded imagination.

I made online contact with César Isabel da Cruz, an amateur author and historian from Mindelo, Cape Verde, who has researched the topic. The ship with corn that sank in 1947 was in fact American. César wrote about it, in Portuguese. Below, on author’s permission, is a summary.

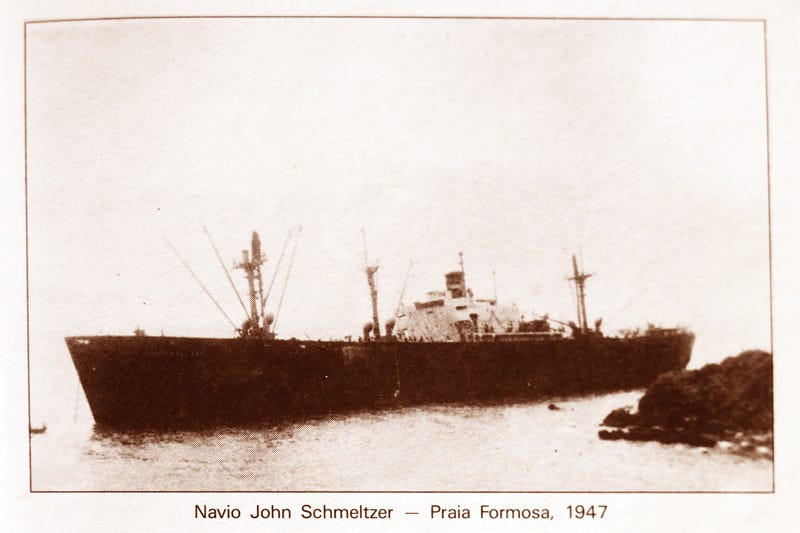

The catastrophe of SS John E. Schmeltzer

Built in 1943 at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard in Baltimore, Maryland, the SS (Steam Ship) John E. Schmeltzer was a cargo ship from the “Liberty Ships” family, mass-produced in the United States during World War II to transport troops and supplies to Europe. After the war, it was assigned to the merchant navy.

On the night of November 24, 1947, the SS John E. Schmeltzer was navigating Cape Verdean waters, traveling from Rosario, Argentina, to Gothenburg, Sweden. It carried 9,000 tons of bulk corn as humanitarian aid to Austria and Germany destroyed by the war.

Around midnight, the captain finished his shift and left to his cabin. Before leaving, he instructed the first officer to wake him up when the lights of Ponta Machado Lighthouse (on the island of São Vicente) would be sighted. What happened then is a mystery.

The night was clear, and weather was good. But the first officer likely saw no light. Or, if he did, he ignored it. During his watch, he did not attempt to determine the ship’s position to see if land was nearby. Around 5:40 a sailor saw something and yelled “land or cloud ahead”. Even then, the first officer took no action. Instead of reversing the course, he sent for the captain. By the time the captain woke up and reached the bridge, it was too late. SS John E. Schmeltzer grounded on the rocks of Canjana, near Praia Formosa, at the southwestern tip of Santo Antão island.

On the island, this was the year of famine. But it was not a regular famine. In Cape Verde in 1921–1922 already, people found themselves in the ‘last stage of naked misery,’ having consumed clothes, earth, and sold jewelry, with over 23,000 people dead. Then again in 1941–1943, over 24,000 deaths from hunger. And finally in 1947–1948, the islands were experiencing drought and famine the most terrible in living memory. The death toll was beyond control.

Upon hearing the news of a ship loaded with corn grounding in Canjana, hordes of starving people from all corners of the island came. Weakened, lacking the strength to endure the long and arduous journey, many perished along the way. Those who managed to arrive, came in rags, or completely naked.

This sounds like beginning of a wonderful rescue story. But historical reality was different. The ship’s crew were concerned about the condition of the ship. No one bothered about thousands of starving people who gathered on the beach.

Initially, the ship was stuck on the rocks by the bow. In an attempt to lighten it and free it, a significant portion of the cargo was simply jettisoned into water. But the waves eventually pushed the ship back on the rocks. Meanwhile, the corn thrown overboard has become quickly contaminated. Due to drought, there was no fresh water available around to wash and cook it.

People rushed to the sea, trying to retrieve corn from the sea floor. Many drowned. Others managed to get to the corn, and soon died from dysentery caused by consuming already rotten corn.

John’s corn could have saved people. Instead, it killed many.

What happened then we know from an account of 22-year-old Alberto Pancrácio Lopes - a Capoverdean, who boarded the wreck the next day, accompanying the head of customs Arnaldo Santos. From now on, all cargo were now under customs control and nothing left the ship.

Commander Pancrácio said the scene of the starving crowds approaching the ship resembled attacks by hordes of Native Americans in Western films. He also recalled seeing more lice than he had ever imagined, on a head of a girl who lunged at a handful of animal feed and choked to death.

Contrary to popular folk tale, no organized corn distribution occurred.

With nothing left to be done about the ship, the crew was eventually evacuated to the United States. The salvaged items, ship, and cargo became the property of the insurers, whose Cape Verde representatives handled recovery, as is standard in such cases.

Alexandre Maria Alhinho, a former Portuguese army sergeant living in São Vicente, was hired for the operation to recover the salvage from the shipwreck. He formed his team with people he brought from São Vicente, and nearby communities.

Under the supervision of customs officials, the corn from the ship was transferred to the ships Carvalho and Bita, responsible for taking it to São Vicente. Mr. Alhinho built an ingenious, makeshift cable car system made of cable and baskets, to transport the cargo. Significant portion of the cargo fell into the sea. It is possible that Mr. Alhinho deliberately let this happen, so that it could be retrieved by the starving population of Canjana.

Meanwhile, people from all over the island arrived in Canjana, camping there —sometimes entire families, or what was left of them. Corn was recovered from the sea bed mostly by sailors and divers from the fishing communities of Janela and Cruzinha.

There was great mortality. Mr. Alhinho had a cemetery, still clearly visible on Google Earth.

It is said that a starving man from Penedo de Janela asked boatmen to take him to Canjana, saying he wanted to satisfy his hunger, even if it was his last meal. They granted his wish. He ate, filled his stomach with raw corn, and died bloated.

Aside from those who settled in Canjana (temporarily), many came to acquire some corn by purchase or barter—offering water, firewood, or agricultural goods—after long journeys. Boats from Janela returned loaded with corn after a difficult crossing. There were even boats from Salamansa in São Vicente. Much of that corn was damaged by seawater and unfit for human consumption. Mr. Alhinho’s company sold part of the corn. Dona Birita, a young housekeeper of the family, said she was instructed to sell good corn to people. The corn spoiled by seawater, she could give away to feed animals. Often moved by compassion, she gave good corn to those who couldn’t afford to buy.

The offloading operations continued through 1948. That year, there was a bit of rain—just enough that some corn from John was planted, and they say there was a harvest in the highlands. Even today, there are those who proudly say they’ve sown or eaten corn descended from the ship’s hold.

In the collective memory of Santo Antao population, this period is known as Time of John (Tempo de John).

Post Scriptum

The story, meticulously recreated by César, finishes here. For more sources:

Review by Heleen Smits of historical novel Time of John, by Pitt Reitmaier and António Pedro Costa Delgado.

Thanks to research of Éder Oliveira from Praia, we know the probable identity of the ship’s captain: Alexander Ekke, who was born 1885 in Saarema, Estónia, then emigrated to the USA.

We also have access to the partial court hearing of the first officer responsible for the catastrophe (1949). His name was Karl M. Skjaveland, of Norwegian descent.

As final note, the island Santo Antão, where the story happened, is worth a visit. I went there too, and wrote some stories. The sea near Santo Antão can be very rough, especially in November.